“Why do good girls like bad guys?” It was a question on the lips of many long before Falling In Reverse released their song ‘Good Girls Bad Guys’ in 2011. The trope of the “good girl” falling for the “bad boy” far predates the soft-metal track. Rigid forms of the bad-boy typecast have existed in pop culture since the ’30s, with films like Rebel Without a Cause, Grease, Cry-Baby, The Breakfast Club and even Disney’s Tangled (no judgement toward anyone who had a crush on Flynn Rider—there’s a reason for it) ensuring its omnipresence in the ensuring decades.

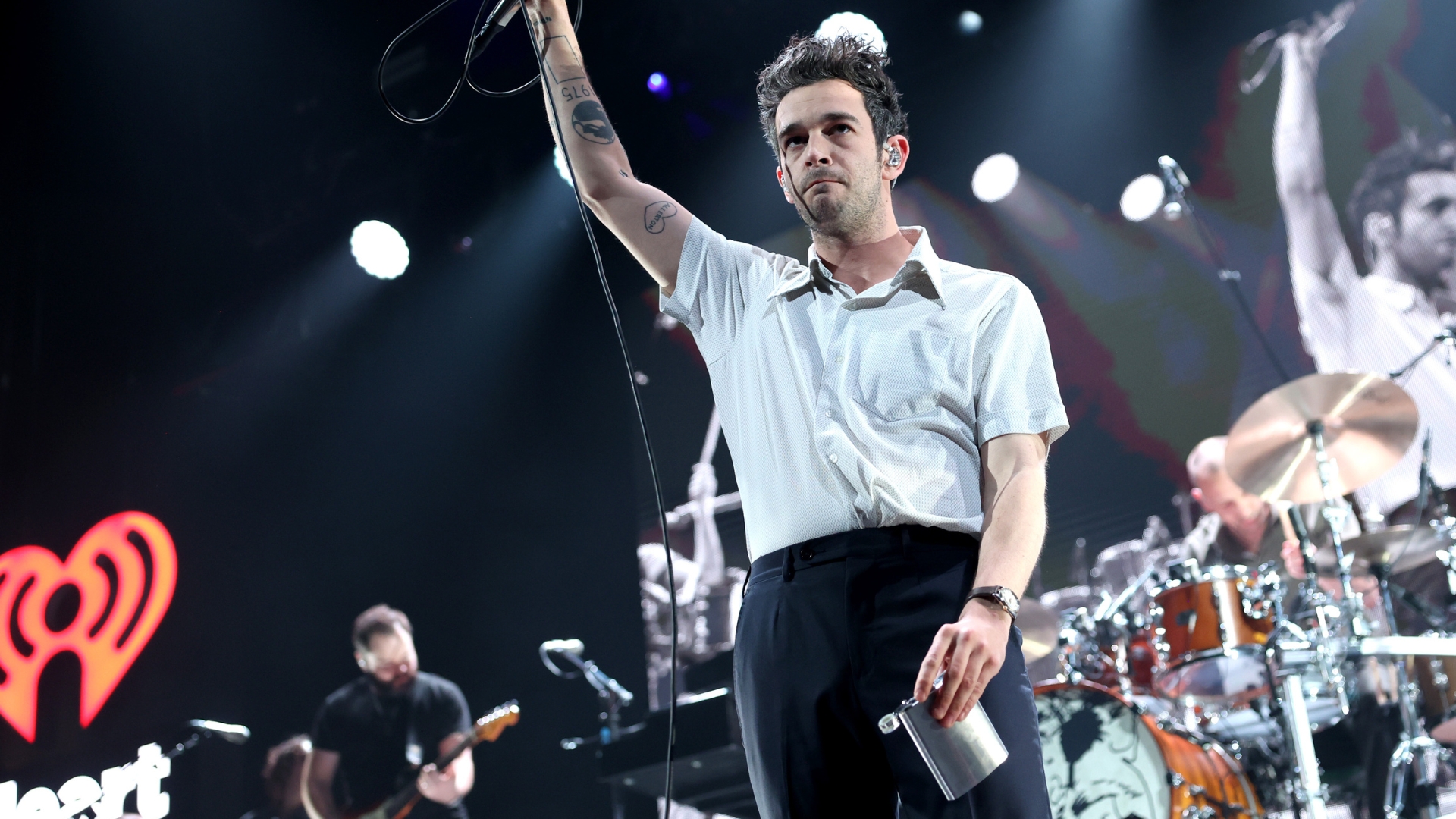

But what exactly makes a so called bad boy? You likely have a mental picture: he may be a rebellious, traditionally masculine figure with muscles, tattoos and a pack of cigarettes tucked in the pocket of his leather jacket. Or perhaps he is a Matty Healy type; a brooding, artistic anarchist. Either way, that tough-guy image comes with a stoicism that indicates there is more to him than meets the eye. He is a mystery waiting to be solved, a gentle being with a tragic backstory that has hardened his outer shell. He is tough enough to be protective but, deep down, harbours a vulnerability that necessitates the care of a partner—a quality that allows filmmakers to gloss over the fact many of these bad boys are, well, bad: bad partners, bad community members and, at times, bad people. Yet, for some reason, we find them attractive all the same – and not just on screen.

Do Girls Really Like Bad Boys—and Why?

Sexologist and relationship expert Dr Gabrielle Morrissey explains that women are attracted to bad boys for a range of biological, evolutionary and socially constructed reasons. When we are falling for someone, our brain releases chemicals called phenylethylamine and oxytocin. “When, in those early dating stages, someone is exciting and thrilling and unpredictable, it elevates all of that and makes you want to experience more of it,” says Dr Morrissey. In a way, that feeling is like a drug.

"Cliches happen because they are repeated so often that they become cliche"

It goes without saying the entire trope is heteronormative, but it is shaped by traditional gender roles more than one might expect. “Cliches happen because they are repeated so often that they become cliche, and those traditional, rigid gender roles definitely lend themselves to women being attracted to bad boys,” says Dr Morrissey. “[Women are] traditionally looking for a provider, power and protection. So if you’re subconsciously looking for that, because you’ve been conditioned and nurtured for it, it’s going to be really evident in your bad boys because they tend to be your bigger showmen—they stand out from the crowd.”

“What has happened is that we have dichotomised those things,” says Annia Baron, a clinical psychologist at the Indigo Project. “We’ve put them in separate categories; you can either be the good girl or the good boy and you’re nice, you’re polite, you do the right thing, you conform and you’re maybe a bit more moralistic. Or you’re the bad, rebellious type who doesn’t conform.”

But no one’s psyche is black or white. Annia says, “If you have been [labelled as] being a certain way but you know deep down your inner world also has shadows … it’s kind of an appropriate channel, perhaps, to express those [darker] behaviours by being with someone who embodies all of that—it’s like it gives you permission to be more like that.”

Throughout our entire lives, particularly as women, we are subject to discourse rooted in moralistic behaviour. We are told what we should and shouldn’t do, what is good and bad behaviour, and the right and wrong ways to recognise and respond to each. Around adolescence, it’s a natural inclination to rebel against this. In a phase that can continue past the teen years, it is normal to want to test boundaries, experience consequences and push limits.

“When we are at an age where we are sexually developing and connecting to that desire … that [rebellious spirit] is so much more powerful,” says Annia. “If someone says, ‘Don’t do that, that person’s not good for you, you shouldn’t be with those kinds of people,’ then already, there’s something in the brain that goes, ‘But hang on a minute—no. I want to self-actualise.’”

Dr Morrissey explains that we also have “types,” which are solidified and reinforced by repeatedly dating the same kinds of people. If you have an attraction to a bad boy in high school or date several in your youth and have good experiences, those encounters are conditioning your mind to find those types of men appealing.

It is unsurprising, then, that younger women in pop culture tend to be portrayed as more susceptible to the bad boy’s allure, whereas mature protagonists are generally able to see through the facade. Think of the Kat Stratfords, Sandy Olssons, Claire Standishs—teenage girls who are repulsed by their respective bad boy love interests, yet come around by the end of the film. This is a theme that may translate into real life, too. As we age, the bad boy appeal can fade.

"As we age, the bad boy appeal can fade"

The initial attraction of a bad boy is largely superficial, driven by that social conditioning as well as a general sense of excitement, which Annia says is “probably like that because there’s a mismatch in your nervous systems or attachment [styles]”. However, once the deeper romantic factors come into play, you may realise you actually have disparate values.

“At the outset, the attraction to the bad boy is that he’s bad—but he understands me and I understand him and so we have this special, romantic dynamic that is wild and exciting,” Dr Morrissey says. “This notion of opposites attracting is not borne out in research and in long-term relationships, it creates friction. But, in the initial phases, that opposites- attract mentality says, ‘Oh, we’ll be a fantastic counterbalance to each other.’”

As we age, we tend to consider these values and deeper romantic factors earlier on in a relationship. Accordingly, as we grow older, someone being hot is simply less likely to draw us in. The real-life bad boy begins to lose his sheen; the nice guys suddenly start looking good. So, love your bad boys on-screen but be warned—that tattooed guy from Hinge who leaves you on ‘read’ probably won’t do a Danny Zuko any time soon.

This article originally appeared in Issue 01 of Cosmopolitan Australia. Get your copy and subscribe to future issues here.